Does past trauma impact educational attainment?

Does past trauma impact on the educational attainment of care-experienced young people? If so, in what way? Are trauma-informed educational approaches available to all, or is it a postcode lottery?

To start with, we need to look at the problem.

According to GOV.UK, there were 263,904 school suspensions during the 2022-23 school year. This was an increase from 201,090 the previous year. Permanent exclusions, i.e. when a pupil is removed from a school permanently and their name is taken off the school roll, increased from 2,179 in 2021-22 to 3,039 in 2022-23.

Whilst these statistics are not broken down into whether these young people were care-experienced, the Department for Education (DfE) have stated that 9.8% of children in care experienced at least one fixed term exclusion from school during the 2021-22 school year.

Suspensions and exclusions aside, the educational attainment gap between young people in care and other pupils still remains wide.

So what can be done about this?

Before we can look at approaches and strategies, we need to look at what past trauma actually is, and how it can affect us all.

What is past trauma?

Trauma can be classed as an emotional response to significant physical or emotional events. It can affect our long term mental health, wellbeing and memory. Trauma can also affect us physically, causing headaches, aches and pains and can also disrupt our sleeping and eating patterns.

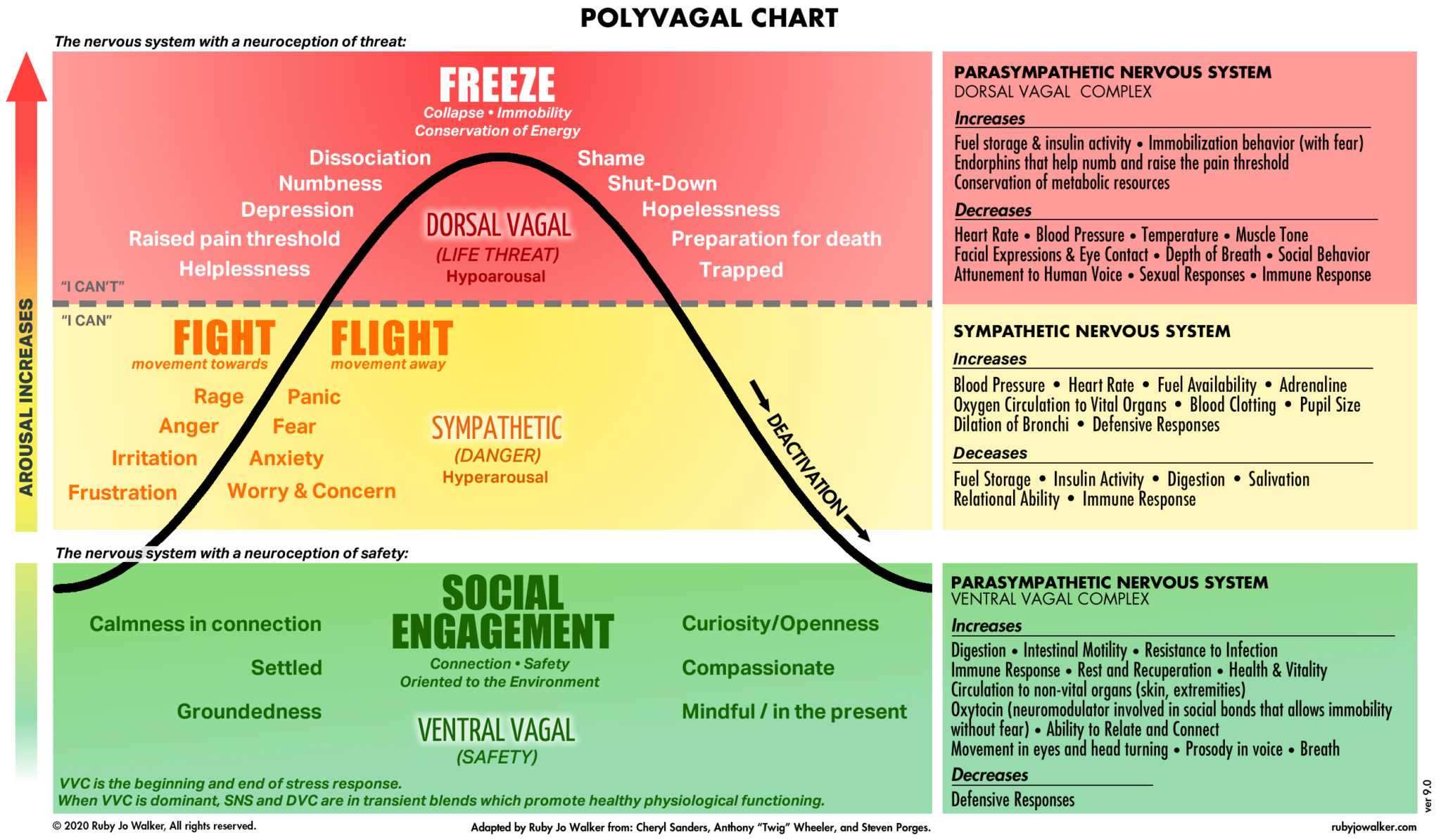

How we respond to trauma in real time can be defined using the traffic light system of the Polyvagal Chart developed by Dr. Stephen Porges in 1994:

The chart highlights the three main psychological and physical states, that neuroceptions of either safety or threat can place us in. We can see that when we are within the Social Engagement state we feel safe, calm and receptive to others. Physically, our bodies are more resistant to infection, and our circulation increases to non-vital organs.

When we experience a degree of threat, we enter the hyperarousal stages of either Fight/Flight or Freeze. We can now see the significant harm these states inflict on our mental and physical health, as our bodies instinctively prepare for danger.

When we talk about ‘past trauma’, we are usually referring to historical events that have not only previously placed us in one of the hyperarousal states, but have conditioned us in terms of how we respond to further actual or perceived trauma-inducing events.

When children experience trauma

When we talk about the trauma that is experienced by children, we generally refer to them as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). There are four main categories of ACEs:

- Physical Abuse

- Sexual Abuse

- Emotional Abuse

- Neglect

Sub-categories of ACEs include domestic abuse, war crimes – and even the process of coming into care. Furthermore, some children may have experienced more than one category of ACE. We must also not forget that witnessing abuse or neglect is also classed as experiencing significant trauma.

Let us now go back to the Polyvagal Chart.

Young people who are dealing with current or past trauma are more likely to reside in either the Fight/Flight or Freeze states. Their senses will be heightened due to actual or perceived threat, meaning that their natural demeanour will not be one of calmness, openness and mindfulness.

By identifying the root of the trauma experienced by a young person, we can start to make sense of their behaviour, thought patterns and any situations that might be activating for them. Only then can we start to formulate relevant strategies and approaches to help that young person self-regulate and begin to heal from the trauma they have experienced.

So how do we even start this process?

A therapeutic approach

You may have heard of therapeutic care or therapeutic parenting. Whatever the context, it is an approach that involves identifying relevant strategies, and then actioning those strategies using a model called PACE (Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy).

Some examples of strategies could be ‘Naming the Need’, which focuses on a young person’s past experiences to help make sense of the present, instilling firm routines and boundaries to help a child feel safe, and short supportive observations rather than grand gestures of praise.

Once relevant strategies have been identified, the PACE model is used to action them. Let’s look at the elements of PACE in more detail:

- Playfulness: using a light tone of voice and expressing a positive outlook will help young people cope with positive feelings that they may not be used to experiencing. A young person who begins to recognise and enjoy the positive aspects of their life is less likely to be withdrawn and defensive.

- Acceptance: accepting a young person’s motives behind their behaviour as something that exists independently from who they are as a person, will help avoid blame and shame.

- Curiosity: displaying curiosity about behaviours, rather than more accustional questions such as ‘why did you do that’, will help avoid defensive responses.

- Empathy: being empathic, rather than sympathetic, displays to a young person that they are understood, and that they are not alone in their sadness or distress.

Employing a planned and tailored therapeutic approach with a young person will help re-route certain pathways in the brain that have become wired in a certain way due to a degree of mental trauma.

Trauma-informed educational approaches

Mainstream educational establishments are constructed for securely attached young people. In other words, those that function within the green ‘social engagement’ state on the Polyvagal Chart. Care-experienced young people, or any child who has experienced significant trauma, could find themselves in a disadvantaged position, through no fault of their own.

A trauma-informed educational approach is essential for children who have experienced adverse childhood experiences, but sadly there is no standardised offering. It can therefore be a real lottery in terms of how inclusive and trauma-informed a particular school is.

Without a full historical record, including details of any activating scenarios gleaned from therapeutic work, young people may find themselves in a reactive environment – where their behaviours are misunderstood and are labelled as anti-social.

If certain behaviours lead to punishments such as suspensions or exclusions, there is a real risk that young people could spiral into criminal activity.

Louise Bomber, a Strategic Attachment Lead Teacher & Therapist, developed a factfile template to record information based around a young person’s relational health, any ‘survival strategies’, main stressors and activating scenarios – and how these present themselves. Additionally, any strategies known to bring a child back to a regulated state.

The factfile is intended to be used in schools as a way to inform all teaching staff of the relevant trauma-informed approaches required for a young person. However, as mentioned earlier, this is by no means a standardised approach.

TACT’s dedicated Education Service is in the process of preparing additional training to be delivered in the schools attended by our young people. But more needs to be done nationally to level the playing field and to standardise trauma-informed approaches in schools.

In other words, to create learning environments where children are understood rather than misunderstood.

Read more about Therapeutic Parenting.