What Is Therapeutic Parenting?

Therapeutic parenting is a parental approach that combines instilling firm boundaries, routines and strategies – along with a model called PACE (Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy). The approach avoids traditional parenting techniques such as ‘time out’ or any other similar punishments. It also discourages reward systems for good behaviour.

The main objective of therapeutic parenting is to re-route certain pathways in the brain that have become wired in a certain way due to a degree of mental trauma.

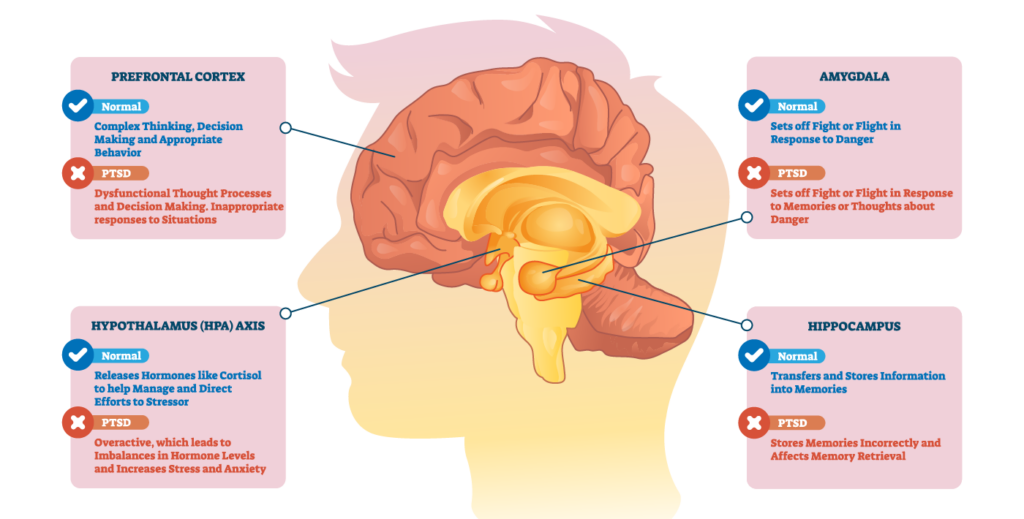

To start, let’s look at the main parts of the brain that trauma affects:

- The Hippocampus. This area of the brain is focussed on learning and memory. Any past trauma will be logged here.

- The Amygdala. This is the area that processes fear and threat. Any degree of mental or emotional abuse will increase activity in this area – heightening a need for safety.

- The Prefrontal Cortex. This manages cognition and is responsible for impulse control as well as an ability to listen and pay attention. Trauma will heighten this area of the brain which can lead to hypervigilance, as well as increased feelings of anxiety.

This means that any child who has experienced ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) is more likely to be hypervigilant of future trauma, preventing them from learning and placing them in a state of high anxiety. They are also more likely to believe that the trauma they have previously experienced will repeat itself.

What are ACE’s?

Adverse Childhood Experiences, or ACE’s, are categories of abuse and neglect defined within The Children Act 1989/2004. There are four main categories:

- Physical abuse

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Neglect

A young person can experience any number of these categories. Each type of abuse will generate trauma, which results in synapses forming in the brain called ‘wiring’. These synapses are linked to the memory – and will impact on their thoughts, behaviour and relationships.

Therapeutic parenting in practice

The main function of therapeutic parenting is to re-route pathways in the brain. The aim is to generate empathy, improve social skills and to create a greater sense of harmony. It will also enable cause and effect thinking, self regulation and will help form secure attachments.

Whilst there are a number of techniques that can be employed, an awareness of a child’s previous experiences is essential before any therapeutic approach can be formulated. In many cases, it should also be fully supported by a social worker.

The most significant collection of techniques is called PACE (Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy) that we will examine in more detail later. It is important to demonstrate empathy, and to provide a nurturing environment. However, a strong focus on routines and boundaries is essential.

Some typical therapeutic strategies are:

- Naming the need. Look at a child’s past experiences to help make sense of their current behaviours.

- Short supportive observations. Children who have experienced high levels of trauma do not cope very well with high praise, so instead make short positive observations (e.g. “Great to see you playing with your friend earlier, you shared the toys very well!”).

- Routines and boundaries. This makes the child feel safe, and should be rigidly adhered to. Any changes to routines should be introduced gradually.

- Time in (not ‘time out’). The traditional ‘time out’ increases feelings of rejection, so children should be kept near their parent/carer until the child is calmer. Use light and relaxed conversation to de-escalate.

- Natural & Logical Consequences. To enable children to learn cause and effect, any consequences must be linked to the behaviour. For example, if a child spends all their pocket money at once, the consequence of not being able to buy any more sweets for the week should be highlighted.

- Showing sorry. Rather than expecting a child to ‘say sorry’, which can lead to increased feelings of blame and shame, a calm explanation of why the behaviour is unacceptable followed by a physical gesture on the part of the child should be sought. For example, a child breaks a vase, the adult explains how precious the vase was to them – the child then helps clear up the mess and then helps to choose a new vase.

- No reward charts. These set unrealistic expectations for the child, meaning they are more likely not to achieve the task in order to be rewarded. Instead, use small ad-hoc treats when they achieve something significant.

Read about TACT’s Therapeutic Support.

What is PACE?

Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy, or P.A.C.E., was developed by Daniel Hughes Ph.D. as a means of connecting with a child who may have experienced trauma due to ACEs. However, PACE approaches can be used more universally with any child.

Let’s look at the different facets of PACE in more detail:

Playfulness

This doesn’t necessarily mean active playtime with a child. It’s more about a lightness of voice tone, and expressing happiness and joy. Ultimately it is an approach aimed at helping children to be open to the more positive aspects of their life – and getting them used to coping with positive feelings. When a young person is laughing or having fun, they will be less defensive and withdrawn.

Acceptance

Acceptance is about letting a young person know that you accept their thoughts, feelings and motives without judgement. This does not mean an acceptance of certain behaviour, which may require firm boundary setting. It’s more about accepting the potential motives behind the behaviour. By applying acceptance in this manner, a child will begin to understand that whilst their behaviour may be curbed, this is not a criticism of who they are, and what has happened to them.

Curiosity

By displaying curiosity about a child’s behaviour, you are informing a child that you want to understand ‘why’ they are behaving in a certain manner. By asking questions that don’t necessarily require an answer, you are avoiding more accusatorial statements such as ‘why did you do that’. Instead, by using phrases such as ‘what do you think was going on there?’, you are removing blame, anger and conflict from the scenario – meaning a child will be less defensive in their response.

Empathy

Being empathic displays to the child that the adult is feeling the sadness or distress that they are experiencing. Empathy tells the young person that the adult truly understands them, and that they will not have to face the stressful situation alone. Becoming a child’s ally will help form a bond of acceptance, understanding and general equilibrium.

The PACE model can be used as a general parenting approach, or it can inform the means of delivering a strategy. For example, looking at the Time In strategy above, a parent or carer may use a number of PACE techniques such as Curiosity and Acceptance in order to de-escalate a situation and to try and understand the reasons behind that behaviour.

Which children require Therapeutic Parenting?

Many children and young people in the care system really benefit from therapeutic approaches, whether that be children in residential homes or in foster care. It is by no means a quick solution or something that will work in the short term. Therapeutic parenting requires a commitment from the parent or carer to learn about a child’s past experiences and traumas, and to apply relevant strategies, usually with the full support of a social worker.

Read more about Therapeutic Parenting on the NATP website.

Read more about the support aspect in our What is Therapeutic Support in Foster Care article.